By Mel Luymes

There’s nothing quite like a field of canola in full bloom, a barley field making waves in the wind, or a group of excited cattle mowing down on a field of clover. They are rare enough to see these days, with corn and soybeans more common.

But there are plenty of farmers who are drawing out their crop rotations with new (and old) crops in order to diversify, build soil health, or just for a fun challenge.

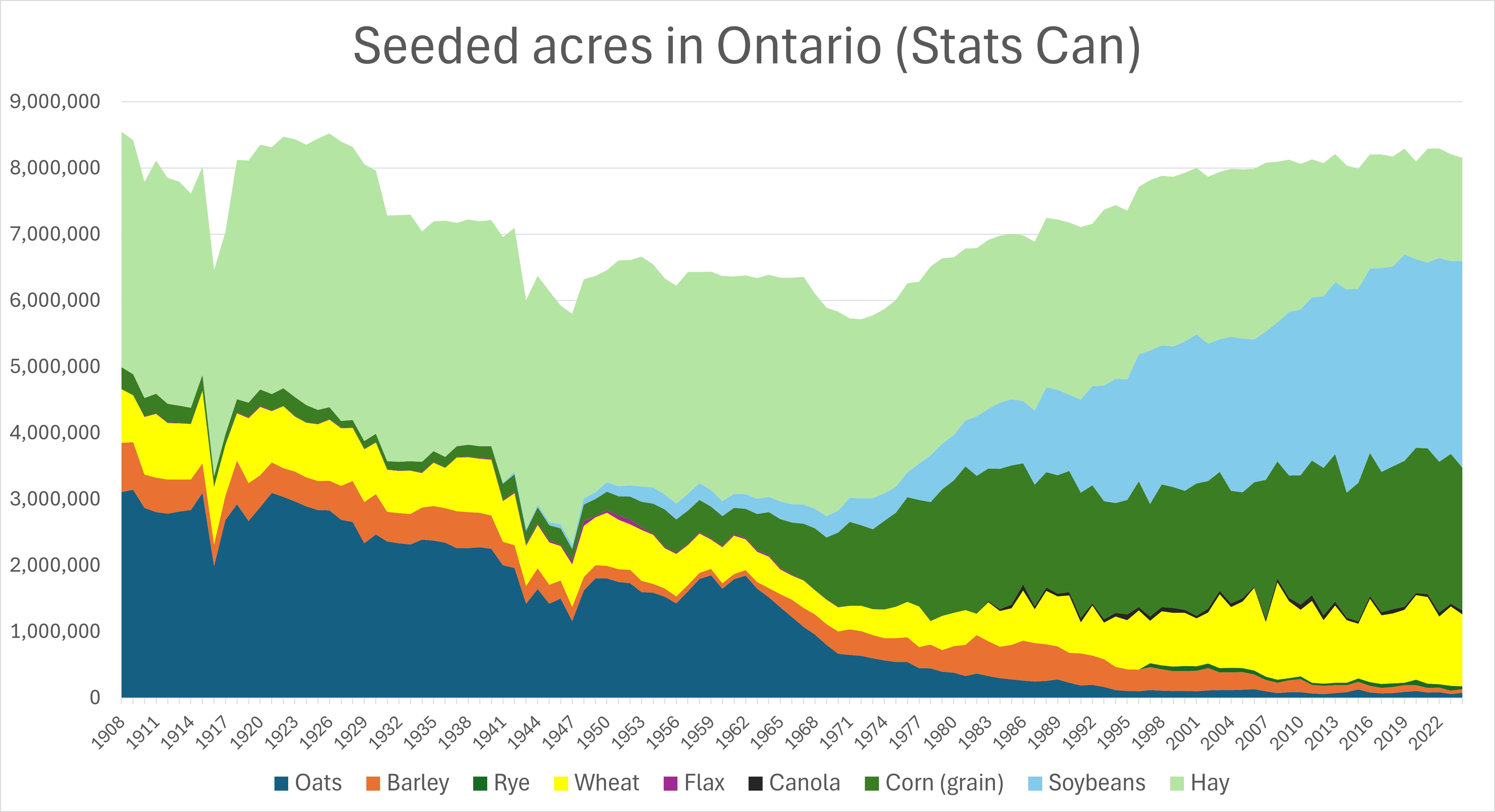

Corn and soybean haven’t always been the king and queen of Ontario agriculture, though most readers will not remember a time when they weren’t. Statistics Canada has records of seeded acres going back to 1908 and just by stacking the acres of oats, barley, wheat, corn and soybeans (and canola, flax and rye for good measure), we can see some interesting trends, including a drastic reduction in seeded acres during World War II, flax being grown (in just a few key areas near mills) until the end of the 1960s and a transition of hay to cash crops starting in the mid-1970s, just about the time when agricultural policy had farmers planting “fencerow to fencerow.”

Corn acres started to take off in the 1960s with new hybrids, a growing demand, as well as harvesting and storage options for farmers. Soybeans, originally a forage crop, started being grown for its seed a decade or two after corn, with varieties developed for Ontario’s shorter seasons. Since 1971, Ontario farmers have seen soybean yields double. Wheat acres have been surprisingly stable in the last 120 years, though we know that yields and varieties for this area have also shifted dramatically over that time.

This chart represents the logical decisions of hundreds of thousands of individual farmers over the years, choosing what to grow; however, these decisions are the result of global demand and prices, local growing conditions and proximity to infrastructure for marketing and processing. With Hensall in their backyards, Huron County farmers have long been putting adzukis, pinto, navy and other edible beans into their rotations.

There are plenty of good reasons to incorporate wheat and other small grains into a crop rotation. Their fibrous root structure is excellent for building soil and because many of them can over-winter, they protect the soil from erosion during the spring melt. Extending crop rotations helps to break pest cycles and it also diversifies a farmer’s income stream.

EFAO Small Grains Program

“Small grains can offer big gains,” says Jackie Clark, the manager of the Small Grains Program for the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario (EFAO). She did her Master’s research at the University of Guelph under Dr. Bill Deen and Dr. Dave Hooker, and she was the inaugural recipient of the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association’s (OSCIA) Soil Health Graduate Scholarship in 2015.

Data from the U of Guelph’s long-term crop rotation trials in Elora show that wheat in a rotation helps to protect the yields of both soybeans and corn, especially in difficult years, says Jackie. While farmers might balk at lower wheat prices, they make more sense when the economics of whole rotations are compared.

Having wheat and small grains spreads out the labour over the year, she adds and the summer harvest of small grains also means there is time to get a cover crop well established.

“We’ve seen the benefits to soil health from cover cropping in research and on-farm for years,” says Jackie. “Specifically, growing legumes in a cover crop means that you are fixing nitrogen for the subsequent crop, and can lower additional nitrogen input needs.”

The EFAO’s Small Grain Program started with pilot projects in 2020, with funding from the Weston Family Foundation’s Soil Health Initiative, to support farmers to put small grains into their rotation. It is a knowledge-sharing network with soil testing and agronomic support, but it comes with financial support as well. The funding is allocated on a per acre basis, through a reverse auction in which farmers submit a bid. Funding is given to farmers with the lowest bids and works upwards until the fund is fully allocated. There are two pools of funding, one for those who have never grown small grains and the other for those who have.

The program is for farmers who are new to small grains, expanding them on new acres or if they haven’t grown any for at least three years. They would be required to plant and harvest a small grain (wheat, spelt, barley, rye, oats, triticale, buckwheat, amaranth, or quinoa) and follow it by a legume or a cover crop made up of at least 50 per cent legumes, whether that is under-seeded or direct-seeded after harvest. The program pays even if the crop fails; it is there to manage risk. And participants are connected to newsletters, on-farm learning and peer mentorship, options for soil sampling and much more. There are also a few farmer-led research projects on small grains, adaptive nitrogen trials in corn following small grains and cover crops (forthcoming), as well as an ongoing project looking at Kernza®, an intermediate perennial wheatgrass, that are (or will be) available on their website, from efao.ca/small-grains or efao.ca/farmer-led-research.

The application takes 30 minutes (or less) to complete and the final reporting takes another few minutes, says Jackie. They purposely reduced the paperwork so that it wouldn’t be a barrier to farmers. There are two intake periods a year, with the next one opening from July 2nd – 15th.

The Pfisterer Farm

Jessica Pfisterer is an EFAO member, a participant of the Small Grains Program and now serves on the program’s steering committee. She and her husband Ryan are first generation farmers, raising a young family near Arthur on 100 acres that they bought in 2019. They started farming with pasture-raised, artisanal livestock, direct marketing of freezer meats and through agri-tourism, but have shifted to focus on selling small grains, soybeans, and growing hay. They have shied away from the high input costs of corn and instead they have focused on oats, winter wheat or mixed grains in their rotation, with plenty of cover crops.

They have a lot of help from Jamie Griffen, who teaches them everything that they didn’t learn growing up on farms, says Jess.

“We call him our farm dad,” she says, “and the boys call him Uncle Jamie, he's been a godsend to get us where we are today.” Growing up in Guelph (Jess) and Conestogo (Ryan), they both have successful careers, but they wanted to farm and have something to pass on to their children. They started on a three-acre property with some small livestock and made the leap when the property near Arthur came for sale. When they moved in, they had a newborn; now they have two sons, and lease an additional 200 acres in Wellington and Dufferin Counties.

Jess continues her day job, in management at a software development company and working from home, while Ryan is on the road managing projects for a telecomms company. They can rarely take time off from their jobs, and instead they have early mornings, late nights and plenty of weekend farming to get the job done. Jess advocates that employees who also run farms should be entitled to 8-10 weeks of job-protected unpaid leave to allow them to farm.

Jess found the EFAO’s Small Grains Program as she was scouring the internet looking for anything that would help them. “It made the decision to use small grains and cover crops easier,” she says. The first year, they bid $100 acre for 32 acres, and she later learned that they had been the last ones funded. The field didn’t have tile drainage at the time and they were a bit concerned about growing barley on it. At nearly $60/ acre, the cost of the cover crop seed was four times more expensive than the barley seed that year, recalls Jess.

For the Pfisterers, small grains and hay are a key part of their farmland leases as well, and they work to find landowners that align on their goals of sustainable soil management.

Cattle in the rotation

Dr. Peter Kotzeff is another participant in the EFAO Small Grains program, and his typical crop rotation involves grazing cattle. He was named the Innovative Farmer of the Year in 2021 and many readers will know Peter as the (now almost retired) large animal veterinarian working at his Chesley clinic. While he sold the practice several years ago to Metzger Veterinarian Services, he still owns the field that slopes down to the Saugeen River on the northeast side of Chesley. The Rural Voice caught up with Peter there, in a lush field of winter wheat.

“What I want to do, I follow the soil health principles, you know, extended rotations, minimal tillage, keep the soil covered, keep a living root in the soil as long as you can and integrate livestock in my farming operation,” starts Peter. He farms 2,300 acres across Grey and Bruce Counties, with one quarter set aside as woodland, wetland and river set backs, one quarter in hay and pasture and one half cropland. He hires local custom farmers to do the field operations, while he focuses on the livestock, on moving and fencing.

Having cattle means that he needs to winter the herd and that his wintering fields will get beat up. He typically uses oats, peas and triticale for a forage that he will harvest, underseeded with clover that he will have grazed and then bale feed his herd there in the snow. The next year, the field will need some tillage, followed by a corn crop which will also see the residue grazed. “For those wintering fields, spring cereals work really well,” he says.

“Some of my land is a little bit heavier,” says Peter, and when it is difficult to get winter wheat in after soybeans, he will use spring cereals and his rotation will be soybeans, oats and then getting winter wheat planted plenty early, ideally in September, with the straw staying on the field. “Oats are not the most profitable per se, but in the rotation, they work really well,” he says. Especially in the northern clays, Peter says that planting wheat in the last week of the season means that it does nothing to protect the soil in the spring.

“Stored feed costs are a major cost in my cow-calf operation,” he says. “Living in the snowbelt of Ontario means limited grazing opportunities after Christmas.” While corn residue can work for grazing after harvest in November and December, he says that the cover crops after wheat and oatlage are ready as early as late August. Grazing these cover crops means the herd puts on a good body condition before the winter, but at the same time it also allows for a longer fall rest period for his pastures, which pay him back in the spring.

As for this field near Chesley, he frost-seeded clover and once this wheat is harvested, he will apply some manure, along with the straw, and after a month or so of growth on the clover, he will bring cattle in to graze it. There is an existing external fence on this field, and Peter wires up an electric perimeter fence, along with internal cross-fencing.

Peter uses temporary fencing to limit cattle to small areas and moves them often to ensure that cattle eat, trample and manure each part of the field, with access to water. Often referred to as “mob grazing,” Peter has more elaborate set-ups on his permanent pastures, but modifies the fencing schemes when he is crazing cover crops. He is hoping to move to Gallagher’s eShepherdTM virtual fencing to solve some of the logistics issues with temporary fencing.

Peter bid $50/ acre to be a part of the EFAO Small Grains Program and says it covers the cost of the cover crop seed. He is grateful for the program and has also given back his learnings to the community, hosting several tours for both cash croppers and cattlemen over the years.

A winter crop rotation

Stuart Wright, of Wrighthaven Farms near Kenilworth, spoke at Grey County Soil & Crop Improvement Association’s (GCSCIA) Annual Meeting in Durham back in December on a panel entitled, “The Fourth Crop.” A dairy farmer, cropping 1,000 acres of land, and a past president of OSCIA, Stuart has thought a lot about soil health and cover crops.

“Instead of planting cover crops for the winter, why not just plant winter crops?” he asked himself. He partnered with Wellington County’s Experimental Acres program to try a completely new crop rotation on 50 acres, starting in 2022.

The Experimental Acres program began as part of Guelph-Wellington’s Smart Cities initiative, and supported dozens of Wellington and Dufferin County farmers with grants of $1,000-$3,000 and some research support for the on-farm experiments they wanted to do. The program has continued and is now available to Grey County farmers as well (see www.grey.ca/experimental-acres).

Stuart planned a winter crop rotation of winter canola, followed by a compost application and then a summer crop of heat-loving and soil-building buckwheat as a cover crop. He then terminated it in September as soon as the buckwheat came to flower, then he planted winter barley, followed by soybeans for the second growing season and winter wheat into the third year. He learned (the hard way) that volunteer canola needed to be managed before the buckwheat was planted.

With the new varieties of canola and cereals, he has high hopes for longer crop rotations to increase the diversity on his farm. He shared some lessons he has learned at the GCSCIA meeting, recommending a plant growth regular (PGR) on the winter barley to prevent lodging, and to make sure crops are sold before they are planted, because they only have a small market at the moment. He works closely with Cribit Seeds / Wintermar Grains for seeds, support and marketing.

Growing canola on the Peninsula

John Rodgers joined Stuart on the panel back in December. He is a farmer near Lion’s Head, a retired teacher and board member of the Bruce Federation of Agriculture, also working with the Bruce Peninsula Biosphere Association. Farming with 2,500 heat units in the Ferndale flats, his fields were formerly the Eastnor swamp; his flat, black soil is 10-15 per cent organic matter.

The area was historically used for cattle (and still is for the most part), with pastures and forages; farmers were only growing corn for silage. A lot has changed in the area in the last 30 years or so, with soybeans only being grown successfully in more recent years.

John first tried growing (spring) canola in 1996. Pest pressures, especially swede midge and flea beetles, have led to ups and downs in canola acres since then, but that could be changing with winter canola. On the Peninsula, winter canola means that it will get the moisture it needs to start, and that it is flowering in cooler temperatures and missing the timing of flea beetle pressures. At 70-80 bu/ac, winter canola typically has double the yields of spring canola.

Meghan Moran is the canola and edible bean specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness (OMAFA) and she estimates that there are about 50,000 acres of canola in Ontario these days, and that a third of that is now winter canola. About 20,000 acres of winter canola was planted in 2024, although with the cold winter and slow spring, not all of it survived.

A newly registered (yet old) variety, Mercedes, has changed the game for winter canola; like winter wheat, has a vernalization requirement, meaning that it needs a period of cold before transitioning to its reproductive stage.

Mercedes canola needs 600 growing degree days before the fall frost (and some nitrogen), so it needs to be planted earlier than winter wheat, which only requires 450 growing degree days. So long as the canola does not bolt before the frost, it will survive the winter and come back in the spring to finish. We will see blooms in late May and a harvest at the same time as winter wheat, allowing some areas to double-crop soybeans.

Canola will branch out and keep putting out flowers and seeds, so on 30-inch centres, they likely won’t mature at the same time. The closer the plant spacing (Meghan recommends 15 inch rows or less), the less variable the yields and the lower the risk of shattering.

Growing winter canola is not for the faint of heart, however. John Rodgers would agree.

The Rural Voice caught up with John at peak bloom on the sunniest day we had seen in weeks. He says it is likely his best winter canola crop to date, but up until a few weeks ago, he wasn’t so confident. When he saw yellow flowers in the late fall, he hoped it was some volunteer spring canola or some off-type seeds, and didn’t mean he was about to lose the whole field. In November, he says walking the field was like walking on water balloons and this spring the field looked really empty, with the smell of rotten cabbage leaves. John was pretty confident that his canola crop wasn’t coming back, that it had been destroyed by slugs or flooded out.

“You just need to avoid driving by it for … quite a few weeks,” John jokes. But he has had several acres of winter canola eaten by slugs in the past, thankfully not by the road. While he started by no-tilling the winter canola, he now feels that managing the residue with some tillage has helped.

The field was planted August 23 last year, after a second cut of alfalfa and timothy, burned down and with two passes of a high speed disc. After this crop comes off, he’ll be no-tilling winter wheat.

When someone in the audience at the GCSCIA meeting in Durham asked John if he would try growing edible beans on the Peninsula, he just laughed. “It’s not for a lack of heat, but a lack of courage,” he says. But it probably won’t be long before John tries his hand at a new crop.

Looking back over the last 50-70 years, did farmers and researchers know how corn and soybeans would transform Ontario’s landscape? And will another crop rise to take the throne? Or perhaps, as the EFAO aims to promote, we will find that the key is to increase diversity and the length of our crop rotations, with plenty of small grains and over-wintering crops included.◊