By Jeff Tribe

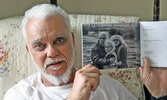

Doug Johnson’s childhood understanding of Owen Sound’s Emancipation Festival was simply that it was a fun, family event.

“To us kids, it was just eating good food, running races, playing baseball and going to the river,” smiled the 75-year-old London resident. “As kids, you’re just kids having fun.”

Johnson has attended the festival for virtually his entire life. His comprehension evolved as a teenager with the realization some of his playmates were turning into attractive young women, onward through marriage and taking his own family and children to the event, and now his grandchildren. It’s still a time of fun, food, musical entertainment and community. But Johnson’s appreciation for its cultural and historical significance for the descendants of Black Canadians who came to the country via the Underground Railroad to settle in freedom has also grown.

“It’s important they keep coming and know their roots, or they’ll lose it.”

Slavery did exist in Canada (British North America), however the British Commonwealth Emancipation Act of August 1, 1834 preceded the January 1, 1863 Emancipation Proclamation in the neighbouring United States by close to 30 years. In that intervening period, enslaved people south of the border sought freedom in Canada, their journey north supported by the Underground Railroad, an affiliation of supportive individuals and organizations.

Beginning in 1862, the original Black settlers spread throughout Grey and Bruce counties and their families, friends and allies began celebrating what was originally known as “Simcoe Day” weekend. A picnic organized through the leadership of British Methodist Episcopal (BME) Church Pastor Thomas Henry Miller and Josiah Henson’s cousin, Father Henson laid the foundation for a century-and-a-half-long tradition. The Emancipation Picnic/Emancipation Festival is the longest such continually-running celebration of Black heritage and culture in North America.

Today, a festival honouring long-standing traditions is hosted by a not-for-profit non-political organization whose mandate is to respectfully honour the hardships freedom seekers endured and their legacies, celebrate the Underground Railroad, and share and appreciate an important if little-understood and under-taught portion of Canadian history, featuring Black contribution.

Johnson’s own family history includes namesake ancestors “coming up” from Kentucky in the 1850s to settle in the Dresden area, as well as the Earls, believed to come from Virginia before stopping near Owen Sound.

“As far as I know, they were escaped slaves looking for freedom,” said Johnson, allowing that precise details from that time period are scant. For years, people didn’t want to talk about horrific conditions endured and escaped. Many stayed silent about enslavement until perhaps sharing a few details late in life.

“You can understand they didn’t want to remember that stuff.”

He can comprehend enslaved people’s desire for freedom.

“They considered you as chattel,” said Johnson, citing the example of a child being wrested from their family. “Someone takes them and sells them and you never see them again.

“Can you imagine what that was like?”

Their journey to freedom was similarly unimaginable, travelling in the dark through unknown, hostile territory, mothers with babies at their breast, in constant fear of recapture, cruel punishment and a return to enslavement.

“How did they do that?” Johnson marvelled.

One historical detail which survived is his understanding that a couple of his ancestors were doggedly pursued by slave catchers, resulting in a confrontation near Detroit.

“There was a big fight there,” said Johnson, one which allegedly ended badly for the pursuers, understandably given what was at stake.

“They would have been beaten and shackled and put back into slavery,” he said, adding his speculation a reward might have been paid even if his ancestors had been returned dead.

Freedom seekers landed at several Canadian destinations including the Niagara region, Ingersoll, North Buxton (Dresden and Chatham) and Owen Sound, which was the Underground Railway’s most northern terminus.

“They wanted to put as much distance between them and their former lives as they could,” Johnson theorized.

His own roots touch down in several of those locations. His father was born in Thorold, meeting his mother in London, where Doug was born. He lived for a time in Dresden, and following a challenging family situation resulting from his World War II army officer father’s struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder - “he came back a mess,” - Doug also spent time with relatives near Owen Sound.

Canada brought freedom, but was not without challenges, including ongoing elements of racism.

Johnson shared the story of his white grandmother being approached by a member of the local constabulary, offering to “run” his father - son of the BME minister - “out of town” for dating her daughter.

“She said ‘Get away and don’t bother us again,’ ” recalled Johnson, adding with a smile, “I’m pretty sure the words coming out of her mouth weren’t Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.”

Doug’s father related how during his six-year military career in World War II, American soldiers from the southern states would refuse to obey his orders until they came under fire, and learned to respect his combat experience.

“And then they started listening to him.”

Johnson’s own experience included the fact he was not welcome to eat in certain restaurants while growing up, and racial slurs flung at him during his career as a talented athlete. It’s history he relates matter-of-factly, undeniably unpleasant, but also something he was not about to allow to beat him either at the hockey rink or in life.

Far less overt, but a factor nonetheless, is historically, Black Canadians were generally a significant minority. As society advances, those in the majority may have occasion to discover themselves in a situation where the tables are turned. Certainly not a negative, just an important realization that what may be a one-time experience is day-to-day reality for many.

The Emancipation Festival has provided annual re-connection for geographically separated families and friends of the descendants of Canadian freedom seekers, and also a rare opportunity for a shared, majority understanding of unique history, challenges, experience and sensibilities.

“When I went there as a little boy I felt I was fine, I was safe,” said Johnson of a prevailing ‘beautiful, serene atmosphere.’

“All you could feel was love and respect.”

Laughing, he shares how typically, there would be little groups at the festival, often defined by age, his own progression landing him among what he used to consider ‘the old people.’

“Time waits for no one,” he smiled, thinking how the passage of time of a passage also brings increased understanding of the festival’s ongoing importance to current and future generations. “It’s important they know it’s special.”

The three-day festival is always the first weekend in August, this year opening August 2 with Speaker’s Corner from 6- 9 p.m. at the Grey Roots Museum & Archives, a themed combination of entertainment and storytelling with an educational component. Presenters may be descendants, historians or educators, says festival board of director Juanita Christmas.

The signature Emancipation Festival and Picnic is held Saturday at Harrison Park from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Official ceremonies are rung in via the town crier. The day also includes educational opportunities, entertainment, vendors and races in keeping with the long-standing tradition of this annual picnic.

Gospel Sunday closes out the festival’s official schedule from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. outdoors at Moreston Heritage Village, beside the Grey Roots Museum & Archives. A shared blessing recognizes its BME origins, at a gathering which has evolved into a musical tribute with speeches honouring history and tradition.

Attendance fluctuates from year-to-year, says Christmas for an event which has been recognized by the City of Owen Sound as “outstanding” for its contribution to culture and diversity.

“We’re just a modest-sized picnic and musical festival, but the impact of preserving this 160-year-plus festival is so much greater.”

Those seeking more information are invited to visit the website https://www.emancipation.ca, or better yet Christmas added, plan on attending in person.

“We’re honouring our Black ancestors and trying to keep our history alive,” she concluded. “Everyone is welcome.

“Diversity is our strength.” ◊